Circus of Dreams (Part 15)

By Asher Crispe: December 5, 2012: Category Decoding the Tradition, Inspirations

To Light Up the Night

If we are ever to understand the scientific circle, we would have to thoroughly immerse ourselves in the meaning of the Samech at the level of the soul power known as gevurah which means ‘might’ in the sense of having the strength to hold oneself back. Gevurah, broadly speaking, entails self-limitation and self-restraint, but on the higher metaphysical level it refers to the process of Divine Creation by means of a contraction (tzimtzum) of unbridled infinity into the confines of a finite world. This withholding or withdrawal of the limitless leads to the natural conformity of all created things. The natural world is the delimited world. Not everything goes. By definition, nature remains internally consistent and self-similar.

If we are ever to understand the scientific circle, we would have to thoroughly immerse ourselves in the meaning of the Samech at the level of the soul power known as gevurah which means ‘might’ in the sense of having the strength to hold oneself back. Gevurah, broadly speaking, entails self-limitation and self-restraint, but on the higher metaphysical level it refers to the process of Divine Creation by means of a contraction (tzimtzum) of unbridled infinity into the confines of a finite world. This withholding or withdrawal of the limitless leads to the natural conformity of all created things. The natural world is the delimited world. Not everything goes. By definition, nature remains internally consistent and self-similar.

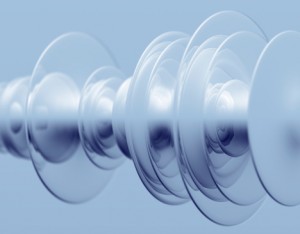

Our image of the Samech as a circle shows up once again within a multitude of elemental features of the world. The question for us now becomes: how is a circle a suitable picture of nature? In Hebrew the word for nature is teva which shares the same root as the word tabat which means a ‘ring.’ From this linguistic connection, the esoteric tradition asserts that nature has identical qualities to that of a circle. For instance, we find that the ring or loop suggests the idea of repetition and recycling. Patterns that follows the same course, that repeat endlessly, that go through the same cycles (such as the seasons…) are essentially predictable. The rotational symmetry of the Samech-circle not only represents a form of equality, it also calls to mind notions of uniformity and internal self-consistency–all of which are required for something to be considered ‘natural.’

The isomorphic aspect of our everyday sense of nature and the mystical cosmology of Lurianic Kabbalah is particularly striking. According to the Arizal, when the infinite light of the Divine withdrew (figuratively) and thus made an empty space (makom panui) or void (chalal) within which Creation could happen (with conscious independence), the form of this vacated area was likened to a circle (although at other times and at different levels there is also a notion of the contraction forming a square). Why use a geometric shape to depict this space? Why does the shape matter?

In response we should emphasize the philosophical significance of figurative numbers. Seeing a number as a geometric figure adds to its overall meaning. In this case, the circle of ‘secularity’ (chalal ‘void’ relates to chol or the profane or secular) has a general uniformity to it. It is all a giant circle (the universe would be ‘one-turn’ or uni-verse in that circle). When we consider that the Divine name for Divinity manifested through the natural world is Elokim, we discover that this name equals 86 which is the value of the word ha’teva ‘The Nature’). This is to say that all of nature is one big natural cycle which is itself just another of the Divine identities.

In Kabbalah we also have a loose approximation for evolution which is the term seder hishtalshelut that means ‘an order of chain-links.’ While the chain itself looks linear from a distance, upon closer examination it is actually composed from scores of interlocking links. Each of these links embodies another non-linear circle whose overlap with the next link in the chain could be compared to a cause containing its effect. The alternating of cause and effect in this Great Chain of Being reinscribes the circle at every stage in the evolutionary development. Our natural world order not only moves round and round within the same circle, it also moves from circle to circle with each new circle becoming another evolution. Evolving may largely be about revolving. The only variation within an evolutionary progression, as the modeling and remodeling of the universe, involves switching back and forth from states of pregnancy (where the effect is latent within the cause) and birth (where the effect gains an identity all its own). The womb of reality from a naturalistic perspective is round and bears another round (iteration) within it (as the effect or child).

When we consider modern day cosmology, the idea of nature as a circle can be found in the presumption of the uniformity of the vacuum of space and the relatively even distribution of the cosmic background radiation. Other assumptions built into our scientific thinking about the natural world include the belief that ‘all else being equal’ which means that when we adjust for local contingencies, the laws of nature should be uniform and consistent throughout all of space and time. The circle abhors anomalies and variations. Thus our inventory of the self-restrictive Samech–nature as a circle–includes uniformity, consistency, commonality, sameness and standardization. All of which are the result of reductionism (tzitzum) which compresses undefined and undisciplined experience to a predictable repetitious pattern.

One of the side-effects of this pretense of Divine withdrawal from the natural world is that the cosmos can appear to be auto-poetic and self-regulating. From the viewpoint of nature, what happens within the vacuum or void is of no consequence outside its part in the causal progression. Nature remains indifferent to what’s happening or who its happening to as long as the rules are adhered to. A rock does not care who steps on it. Gravity does not reverse itself for celebrities. The king or president must eat and sleep just like I do. We are all in the same ‘natural’ circle, the same boat. Sometimes this is experienced as an averaging out of our existence. Our exceptionality is leveled by the seemly tragic indifference of the ‘airtight’ vacuum (whose privation ultimately involves Divine revelation). Stephen Crane (1871-1900) beautiful captured the severity (gevurah) of this situation when he wrote in War is King (1899):

A man said to the universe:

“Sir I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

According to the Ba’al Shem Tov, our consciousness of living in the void (the circle drained of the super-natural, or conversely reduced to a traceable finite circle) is just an illusion. While it may seem inescapable, the problem is all in our perception. No perfect circle or enclosure exists. The natural both sweats out and soaks up the supernatural. The circle remains open. Causal chains may be broken.

For this reason we are instructed in Kabbalah to privilege the Samech-circle of lovingkindness (chessed) which establishes the universal condition as one where ‘everything is [ultimately] good’ over the Samech-circle of severity (gevurah) where everything is universally void and devoid of real significance beyond its place in the natural order. In this way we can instill a notion of care for the well-being of each individual within a universe whose outward appearance is one of harsh indifference. Then, the fact that each of us exists becomes the matter of greatest obligation. Kindness serves as the lever for uplifting the whole of nature. One circle supports (Samech) another.

For this reason we are instructed in Kabbalah to privilege the Samech-circle of lovingkindness (chessed) which establishes the universal condition as one where ‘everything is [ultimately] good’ over the Samech-circle of severity (gevurah) where everything is universally void and devoid of real significance beyond its place in the natural order. In this way we can instill a notion of care for the well-being of each individual within a universe whose outward appearance is one of harsh indifference. Then, the fact that each of us exists becomes the matter of greatest obligation. Kindness serves as the lever for uplifting the whole of nature. One circle supports (Samech) another.

For Part 16 in our series, our attention turns to the aesthetics and harmony of our circle.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/circus-of-dreams-part-16/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/circus-of-dreams-part-14/

Circus of Dreams (Part 15),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)