When Up is Down (Part 7)

By Asher Crispe: May 30, 2014: Category Inspirations, Thought Figures

Kabbalistic Reflections on T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door never opened

Into the rose-garden.

T. S. Eliot Burnt Norton I

What is memory if not the suturing of the fissure of fragmented time? Forming memories takes on the appearance of branches in our neural network. The real life choices between one path and another, the key transitions, the openings, the connections, are forged within the brain as the equivalent of passages and doors. As the popular expression of Hebbian theory goes: “neurons which fire together, wire together.”

What is memory if not the suturing of the fissure of fragmented time? Forming memories takes on the appearance of branches in our neural network. The real life choices between one path and another, the key transitions, the openings, the connections, are forged within the brain as the equivalent of passages and doors. As the popular expression of Hebbian theory goes: “neurons which fire together, wire together.”

Yet, they could have linked up differently. They can be rewired. Even now, in our mind’s eye, we can imagine rerouting the signals “down the passage which we did not take towards the door never opened.” When we realize that recalling an experience and living though it are virtually indistinguishable as far as the brain is concerned, then the shadow world of memory feels the nostalgia for both the past and its alternatives. Robert Frost’s Road Not Taken remains in the rearview mirror alongside the one that was.

If one employs a modicum of artistic license with the mental map, it is easy to see it transfigured into a tree–a living tree and perhaps even a ‘giving tree.’ The tree trope for memory enjoys a privileged status in Kabbalah. It is hinted at in the writings of the Arizal (Rabbi Yitzchak Luria) in the sixteenth century via all sorts of mathematical and linguistic analogies. For the kabbalist, the overall faculty of memory is synonymous with chochmah or the power of intuition and introspection. Therein is planted the tree of life or the ‘living tree,’ the dynamic tree, the tree whose fruit or creative expression permits one to ‘live forever’.

Does not memory immortalize? We do not mean to suggest that one merely lives on the minds of others in the traditional sense, but rather there is some sort of universal memory, a record of everyone and everything, an indestructible black box recorder with the entire trajectory of life and the details of our experience preserved so that they might live again.

In the symbolic universe of the kabbalists, each Hebrew letter has a host of associations, many of which hang onto qualities of the ten powers of the soul or sefirot. Given the present analysis, the aspect of the mind termed chochmah or intuition–with its recollective capabilities which are bound to the ‘depth of the past’ (omek reishit) according to the Book of Formation (Sefer Yetzirah)–appropriately relates to the letter Yud (י). Overall, the Yud graphically resembles a point, or more specifically, a seed. Termed ‘abba’ or ‘father’ in the Zohar, it follows that memory and/or intuition ‘fertilizes’ the mind. This relatively masculine function finds additional support in that the word for memory is ‘zachor’ in Hebrew which also means a ‘male.’

However, the Yud is also subject to being spelled out according to its name (which is also the way in which it is articulated [Y-u-d or Yud-Vav-Dalet]) thus bringing two additional letters into the picture. This is called taking the filled out (milui) form of the letter in order to lay bare its pregnant potential. Nested in the Yud is a Vav and a Dalet which themselves are figurative. Visually the Vav (ו) approximates a line but it is often likened to a passage which connects (Vav as a name means to ‘connect’). Finally, the Dalet (ד) looks the part of a partial frame (a complete frame is comprised of two of these letters with the second Dalet being inverted so as to make a square). A Dalet also etymologically relates to a delet or ‘door’. So we have every seed memory (Yud) filled with both ‘connecting passages’ (Vav) and ‘doors’ (Dalet).

Attacking the thicket of allusions from a slightly different angle, we might cite two additional correspondences. First, we find that above and beyond the Hebrew letters carrying cryptic significance in their names, numbers, and forms, the same forms of exegesis are conferred upon the Hebrew vowel marks as well. Generally speaking, each vowel teams up with a different power of the soul and in this case, the vowel which aligns itself with chochmah (memory/intuition) is called patach which expresses an ‘openness’ to the new—the inception of novel insights into the conscious mind.

An open mind is thus one which permits the influx of content from outside itself–from the unconscious wherein our memories and potential insights are stored. Within the unconscious we encounter the vowel known as kamatz which indicates ‘closure’ (literally a ‘closed hand’). Consequently, the open-closed dynamic serves as the door which swings back and forth between the conscious mind and the unconscious. It filters the abyss of the unconscious and prevents it from flooding all of consciousness at once. While we might want to travel through all ‘doors’ at the same time in a sort of quantum superposition, this is not possible (at least within the confines of ordinary consciousness).

Secondly, one of the fundamental features within chochmah (memory/intuition) is described in the Book of Formation (Sefer Yetzirah) as a structure of thirty-two wondrous pathways. Thus, there are private passages (netivot) or pathways within memory which present us with the challenge of retracing our steps along the same pathway due to both the labyrinthine complexity and the fact that the paths are regrown continually and given (for better or worse) to the distortions of neuroplasticity. One must consider whether or not any passage or door is perfectly repeatable given the propensity for future experience to make alterations to the extent that it now feels unexplored and unfamiliar.

Perhaps, the melancholic tone of Eliot’s verses needn’t transport us to an unfortunate turn of events, a series of poor choices, or a litany of squandered opportunities. Instead, it could be looked upon as the facing up to the forming and reforming of memory, to the marital bond of old and new, and to the finite character of soul bounded by space and time.

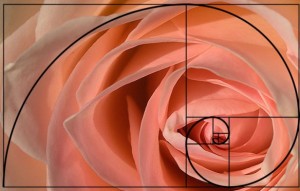

What of “footfalls echoing in the memory”? Are these the sounds of what we are missing? The vestige of the past? A phenomenology of absence? Returning once more to the Arizal on memory, we can expound upon his use of Fibonacci numbers to convey the essential nature of memory. (A brief note on Fibonacci numbers: they are constructed from the addition of the first two numbers in the series [1 + 1 = 2] and then the second and third numbers add to give the next number [1 + 2 = 3] and so on [2 + 3 = 5, 3 + 5 = 8, 5 + 8 = 13, 8 + 13 = 21 etc…]. Hence, we could simples write: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233 in order to have the first 13 numbers in the series.)

In Kabbalah it has been proposed that Fibonacci numbers, which are pervasive throughout the universe, be referred to a mispari ahavah (“love numbers”) on account of any two consecutive numbers acting as the ‘parents’ which give birth to the next number as their ‘child.’ But what does this have to do with memory? If we think back to our word for memory (zachor) we can calculate its numerical value (Zayin = 7 + Kaf = 20 + Vav = 6 + Reish = 200) and we arrive at a sum of 233 which is our 13th Fibonacci number which we listed above.

While this might seem like a trivial allusion, the mystical tradition is replete with references to such proportions. Anyone who has studied the Fibonacci numbers knows that they ‘miraculously’ show up in nature across a wide range of scales from the basic design of the human body all the way up to the spiral disk of the Milky Way galaxy and beyond. They are nature’s memory. They surface in art, architecture, music, biology, astrophysics, botany, and more. Likewise, they supply a method to the madness of memory formation. While this is a topic which far exceeds the present discussion, let us merely state that it is a subject that merits further investigation.

Along side ‘memory,’ another important gematria (numerical equivalent) to be mentioned is that of the etz hachaim or the “Tree of Life which is also 233. This comparison emphasizes what we said earlier about the arboreal networks of memory in the mind. Rather than stopping here, we might suggest that if we want to stage a conversation about kabbalistic ideas atop the Four Quartets, then the particularities of Eliot’s word choice are also fair game. Why “footfalls”? In the Chassidic tradition of commenting upon the technical imagery of Kabbalah, the understanding is that the foot is the lowest part of body. Moreover, it is the part which connects with the ground. It interfaces with external reality more than the rest of the body as we move about in our daily routines.

Sometimes, the general division of the body splits the self into head, heart and foot in order to draw a parallel to the cognitive, emotive and behavioral. When we recall something in memory, there is something akin to active and passive memory. The shifting sands and howling winds of thought and feeling evoke a tempestuous conception of memory, but the idea of receiving a fixed recollection—which in turn secures a basis of comparison when we rewind our lives and watch the slow-motion instant-replay with the expectation discovering nothing new—purports to be foundational. Our introspection ‘stands’ upon it.

In Hebrew, the word for foot (or leg) is regel which very well might have inspired the English word ‘regularity.’ Certainly, in the light of Chassidic philosophy, it marks the sphere of the behavioral. The steps we take ‘on our feet’ are ‘algorithmic.’ We calculate our moves. We assume discreet positions. We self-evaluate based on our programatic choices. Selection. One memory. One possibility. One actuality. One passageway. One door. All else is excluded.

In Hebrew, the word for foot (or leg) is regel which very well might have inspired the English word ‘regularity.’ Certainly, in the light of Chassidic philosophy, it marks the sphere of the behavioral. The steps we take ‘on our feet’ are ‘algorithmic.’ We calculate our moves. We assume discreet positions. We self-evaluate based on our programatic choices. Selection. One memory. One possibility. One actuality. One passageway. One door. All else is excluded.

A path dependent image of memory—the tracing of the branches of a living tree—is but the inscription of regulation upon memory (a ‘footfall’). It is not the first ‘sound’/impression but the reverberation that is makes–the echo. We are distanced from the object which we cannot perceive directly but only pick up on as it ‘bounces off us.’ Moreover, regel (foot) also equals 233 (our Fibonacci number and the equivalent of memory). As such, it suggests the ‘habits’ of memory or the ‘behavior’ of recollection. It is foremost what we do with our memories and what they do to us. It grounds or anchors our memories in concrete people, places and things whose objective concrescence haunts the inner chambers of the soul and cements our sense of loss.

We feel the pain of these exclusions especially in the rearview mirror. What comes next around blind curves on darkened roads which may or may not lead to dead ends, retroactively throws us back on our recollections. We analyze the patterns. We are stupefied. Not being able to more forward until we contend with the past brings us in close proximity to the rose garden. Somehow, we know we must go there next.

And go there we will! A tour of the rose garden, its Jewish history and psychological import awaits us in Part Eight.

We wish to dedicate this series of articles to the memory and elevation of the soul of Yaakov Ben Tzvi Hersh (Ballan) whose soul should experience the reality where ‘time present and time past’ are both definitely ‘present in time future…May his soul be bound in the bundle of life. –The 5th of Tamuz 5772.

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/when-up-is-down-part-8/

http://www.interinclusion.org/inspirations/when-up-is-down-part-6/

When Up is Down (Part 7),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)