Glee and Television’s Taste for Inadequate Representation

By Asher Crispe: December 16, 2010: Category Inspirations, Living with the Times

Teen shows, high school dramas, coming of age series, are always filled with the growing pains that we never seem to grow out of. As one of the hit new TV series, Glee stakes out ever scarier ground on the path to becoming a someone. Maturation twists personal identity into perpetual identity crisis. Some say this show has its hand on the pulse of the cyber teen digital natives with showbiz and popularity aspirations so I am going to go with it. As far as I can tell, the cast is trying to figure out who they are and then sing about it.

Since high school, or maybe school in general, seems to be about clicks, fitting in or standing out, social status and positioning, the currency of this strangely familiar but alien world, is a serious laughing matter. Take for instance, a pivotal episode like Mash Up, number 8 from season one, where many of the characters start to present as more complex. The whole show on some level is embodied in this one episode title. Mash up’s do go a long way to defining the ‘functional’ qualities of a generation. Equipped with easy access to high performance digital tools, music and video are readily augmented for those with a taste for synthetic ‘something from something’ novelty. The same holds for real life, as the show explores how football players can be in the Glee club, losers can be cool and cool people can be losers. Old social codes are clashing more and more with the range of self expressions the students are drawn to and the result is a mash up of cut and paste personal identity.

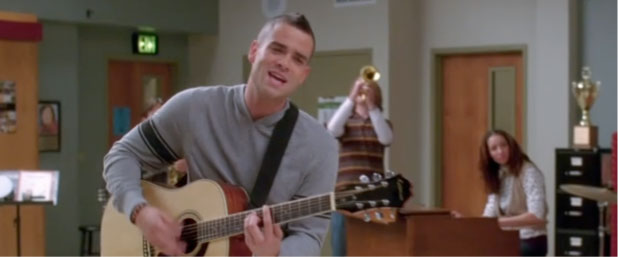

Somewhat more interesting, from a Jewish perspective, has been the show’s wrestling with questions of Jewish identity. This is due to there being a number of the key characters who are Jewish on the show. In Mash up, Puck, a mohawk sporting, pool cleaning, brutish football hazing champion, suddenly airs his mental radio and we realize he has thoughts atypical to his square rough and tough exterior. What is revealed from his inner world? Oddly, that he is Jewish and that his mother wants him to date a Jewish girl, resulting in him trying to court Rachel, the overly ambitious awkward diva in training. We actually hear this while watching his family watch Shindler’s List on Simchat Torah.

Somewhat more interesting, from a Jewish perspective, has been the show’s wrestling with questions of Jewish identity. This is due to there being a number of the key characters who are Jewish on the show. In Mash up, Puck, a mohawk sporting, pool cleaning, brutish football hazing champion, suddenly airs his mental radio and we realize he has thoughts atypical to his square rough and tough exterior. What is revealed from his inner world? Oddly, that he is Jewish and that his mother wants him to date a Jewish girl, resulting in him trying to court Rachel, the overly ambitious awkward diva in training. We actually hear this while watching his family watch Shindler’s List on Simchat Torah.

The irony for those who don’t know this reference, is that Simchat Torah is considered to be the most joy filled day of the Hebrew calendar as it celebrates the connection that every Jew has—learned or not—to the Torah. This is a festive day of dancing with a Torah scroll and not a day of mourning as suggested by the teary eyed mother watching a Holocaust film. Had they picked the 9th of the Hebrew month of Av, a fast day mourning the destruction of the Temple, it would have made sense but lost the irony or joke (depending on whether the writers knew the difference and made this ‘mistake’ intentionally). What this highlights however, is the fact that the so called Hollywood contingent of Jews has an unprecedentedly large microphone and stage with which to work out personal and social issues of Jewish identity in a very public venue. In a rather subtle way, this scene captured the sense of discontinuity between the partial tradition that many Jews have been handed as to the need to preserve their Jewishness without substantiating it in a complete and positive way. Any suggestion of the Holocaust and that classic sense of Jewish guilt is aroused momentarily. As the show moves on, this motivation to connect to something Jewish flares and then ultimately fizzles out.

To turn a philosophic corner, the question of Jewish identity is enmeshed in the quest for clarified personal identity on the whole. Ever since self-conscious beings cut up their world and life experience into appearance and reality, we have been faced with an uncomfortable dualism: are we as we seem or does a surplus of self lie beneath the radar?

To turn a philosophic corner, the question of Jewish identity is enmeshed in the quest for clarified personal identity on the whole. Ever since self-conscious beings cut up their world and life experience into appearance and reality, we have been faced with an uncomfortable dualism: are we as we seem or does a surplus of self lie beneath the radar?

Which is like that part of me that is totally missed by the cheerleaders:)

All of this takes us headlong into questions of representation. What can be predicated of a subject—can A be said to equal B—is this just a more formal way of playing dress up, of masking real people in elaborate conceptual clothing? In short, if you are asking if the description fits or sticks when referred to the other, you are riding this same line of reason.

In general, “concepts,” like teenagers, have been having a tough time. Philosophers (the professional sort as well as the half time amateur) were once high rollers with endless credit, endeavoring to leverage the whole world with a good set of high class “concepts,” posh “descriptive ideas” or sugar coated “categories”. Their critics, time and again, have been known to weigh in with a margin call, and the vast empires of thought go tumbling down. Perhaps it is the act of painting each other that arrests our natural flow and development. After all, why can’t a football player be in Glee club? Perhaps modernist writer extraordinaire, Robert Musil best surmises the difficultly insisting in his work The Man without Qualities that “a concept is living thought killed, never to stir again.”

Alternatively, we could label the problem under the heading “idols of the mind” in the sense of the 17th century Novum Organum of Francis Bacon. It is remarkably easy to go from idea to ideal to idol when mediating one’s experience with cognitive filters. The Divine, in Judaism, is ultimately the unrepresentable, the excess or abundance of meaning that overflows all descriptions. The prohibition of idol worship is the ultimate critique of representational thinking. Moreover, the Divine essence is the spark of all created beings according to Jewish mysticism. Therefore, each and every one of us has a concealed core that escapes definition. In practice, Jewish ‘identity’ begins with the refusal of all idols—an act tantamount to resisting the tendency to solidify identity in a fully graspable finite form. The infinitization of the individual respects a persons capacity for change, delays or ameliorates judgement and offers only a modest sense of knowing.

Watching Glee, like many other shows, the audience cannot help but feel that they have a different awareness of the characters than the characters have of themselves. We are forced to confront that parallax gap between what they seem to be and who they are. This is a world of floating perceptions as mashable as the music they sing. The shows conflict, comedy and drama is then driven by inadequate representations dancing before us.

If we take this our of the fictional universe for a minute, we can entertain a key theme in Kabbalah which is the notion of a tzimtzum or contraction of the Divine that was required to create the world. The revealed infinity from before creation was in a sense concealed and therefore permitted the emergence of a finite reality. This process could be termed a ‘reductionism’. From the notion of tzimtzim, we can learn something striking in the realm of the interpersonal. In the world, the encountering of the other—even one’s peers in high school—is often fueled by reductionist tendencies. We emulate the Divine act of creation in creating our own world of finite representation. This impacts that way we see ourselves and others in that we accomplish this by contracting all of the inexpressible infinitely into the finite containers of consciousness, living from concept to concept in trial and error. Let’s see if Finn, Quinn, Rachel, Noah and the rest of the cast, can sing their way out of this one. As a matter of Jewish practice, flipping the contraction back on itself, entails a lifetime of work to restore the infinite dimensions to a limited social world.

Now give me a beat…..

*Note: all screen shots copyright of FOX broadcasting company

Glee and Television’s Taste for Inadequate Representation,

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

Really compelling analysis. I leave with the message that the next horizon is for a new contingent of Jews to substantiate our Jewishness through artistic exploration in a complete and positive way! Those currently working out their struggle with Jewish identity in Hollywood are clearly having a pintele yid crisis but they don’t have access to the higher knowledge their souls are craving. We have to provide that spiritual substance in forms they can relate to, right?