Out of Touch (Part 5)

By Asher Crispe: June 8, 2012: Category Decoding the Tradition, Inspirations

A Phenomenology of Involvement without Interference in the Rabbinic and Philosophic Traditions

Touching and not Touching as Rectification and Redemption

—To gain such perspectives [perspectives that reveal the world in a ‘messianic light’] without willfulness or violence, entirely from felt contact with its objects—this alone is the task of thought.

Theodor Adorno (40)

—When I saw an external object, my awareness that I was seeing it would remain between me and it, lining it with a thin spiritual border that prevented me from ever directly touching its substance; it would volatize in some way before I could make contact with it, just as an incandescent body brought near a wet object never touches its moisture because it is always preceded by a zone of evaporation.

Marcel Proust (41)

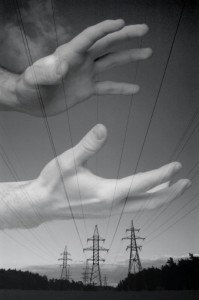

The questioning of touch, of the handshake, of its uses and excuses beckons in the midst of our social ventures. Understanding the ramifications of touch may provide the necessary key to transform both self and world. Depicted in rabbinic exegesis as a double bind where we don’t have the choice to touch or not touch, or more precisely we chose touching and not touching—not touching as touching and touching as not touching—which is the image of hovering.

The questioning of touch, of the handshake, of its uses and excuses beckons in the midst of our social ventures. Understanding the ramifications of touch may provide the necessary key to transform both self and world. Depicted in rabbinic exegesis as a double bind where we don’t have the choice to touch or not touch, or more precisely we chose touching and not touching—not touching as touching and touching as not touching—which is the image of hovering.

This hovering best reflects the involvement without interference of the Divine—the extreme of infinite care and responsibility teamed with infinite freedom. As the verse in Deuteronomy lauds God’s kindness to Israel: “He was like an eagle arousing its nest, hovering over its young…” (42) Rashi’s explanation of “hovering over its young” is as follows: “He does not press himself on them, but hovers, touching and yet not touching.” (43)

From here we see the translation of hovering into the touching and not touching structure that we have advocated. Touching “tactfully” compares God the eagle with Israel His children in a parent-child relationship. If the parent weighs down upon the child, this overbearing influence will crush and suffocate the child. Children crave freedom. Micromanagement of children by parents interferes with the proper development of the child who will gain no sense of independence. However, if the parents stay too distant and extend too much freedom to the child, this will inevitably be interpreted as a lack of care to be involved in the child’s life. So the eagle hovers—proximity transmits warm concern and all is left tactfully intact.

Turning back, the phenomenon of hovering finds messianic expression in the interpretations of one of the most “primordial” verses of the Torah. Genesis announces a world of chaos and void that promises to be transformed into a place for the Divine Presence. “…And the Spirit of God hovered over the surface of the waters.” What is this “Spirit of God?” The Midrash here too explains “hovering” as “touching and not touching” only the Spirit of God or Godly Spirit that hovers is that of the Messiah. (44) The world as seen through the lens of redemption is a world that hovers “touching and not touching.” (45) Could these ideas be echoed any louder in Adorno or even in Levin’s own personal formulation where: “Not touching would accordingly be a gesture of respect for the promise of a messianic era?” (46)

Turning back, the phenomenon of hovering finds messianic expression in the interpretations of one of the most “primordial” verses of the Torah. Genesis announces a world of chaos and void that promises to be transformed into a place for the Divine Presence. “…And the Spirit of God hovered over the surface of the waters.” What is this “Spirit of God?” The Midrash here too explains “hovering” as “touching and not touching” only the Spirit of God or Godly Spirit that hovers is that of the Messiah. (44) The world as seen through the lens of redemption is a world that hovers “touching and not touching.” (45) Could these ideas be echoed any louder in Adorno or even in Levin’s own personal formulation where: “Not touching would accordingly be a gesture of respect for the promise of a messianic era?” (46)

Where are we left? What can we conclude? As insolvent as these questions are, we can assert our right to embrace contradiction—where we speak against ourselves—making gestures and then withdrawing them. We hover in the middle—the excluded middle. The only embrace remaining is of the unreasonable paradox. We may in the end believe our beliefs and doubt our doubts. There is no greater surety than that, in the words of Jean-Luc Nancy: “…the body never ceases to contradict itself. It is the place of contradiction par excellence.” (47) We can only quiver in such a place or non-place as the case may be. Nancy cultivates life in this “between” where:

Everything, then, passes between us. This “between,” as its name implies, has neither a consistency nor continuity of its own. It does not lead from one to the other; it constitutes no connective tissue, no cement, no bridge. Perhaps it is not even fair to speak of a “connection” to its subject; it is neither connected nor unconnected; it falls short of both; even better, it is that which is at the heart of a connection, the interlacing of strands whose extremities remain separate even at the very center of the knot. The “between” is the stretching out and distance opened by the singular as such, as its spacing of meaning. That which does not maintain its distance from the “between” is only immanence collapsed in on itself and deprived of meaning.

From one singular to another, there is contiguity but not continuity. There is proximity, but only to the extent that extreme closeness emphasizes the distance it opens up. All of being is in touch (my emphasis) with all of being, but the law of touching is separation; moreover, it is the heterogeneity of surfaces that touch each other. Contact is beyond fullness and emptiness, beyond connection and disconnection. (48)

From what will this save us—attempting so delicate a balance? Again harvesting from the wealth of Levinasian descriptions, Levin aids our accounting of the prohibited contact, of the revulsion to hold the hand of the other too long in the gesture of the handshake; where comfort quickly gives way to discomfort because:

…when contact between two persons is prolonged, and the touching becomes mere “palpation,” then the “intactness” of the other is being violated for the sake of knowledge. Palpation is the objectification of the other’s body, a reduction of the other to a tangible possession—in effect, an obscene form of knowledge. (49)

Taking a lesson from Derrida, who dedicated a magnificent volume to Nancy’s theories of touch, we get a rare glimpse of their unusual intellectual friendship—how they touched upon each other and left many impressions to be signed and reassigned. Our redemption requires that:

…one should understand tact, not in the common sense of the tactile, but in the sense of knowing how to touch without touching, without touching too much, where touching is already too much….By essence, structure, and situation, the endurance of a limit as such consists in touching without touching the outline of the limit. (50)

Letting our thoughts linger on a second helping of Derrida, from a meal of which we are always stuffed and yet can never be too full, we pause alongside the law, a rabbinic law, a law that touches upon touch in the absence of touching, the איסור נגיעה [literally ‘prohibited touch’ or issur negiya], where:

The law in fact commands to touch without touching it. A vow of abstinence. Not to touch a friend (for example, by abstaining from giving him a present or from presenting oneself to him, out of modesty), to not touch him enough is to be lacking in tact; however, to touch him, and to touch him too much, to touch him to the quick, is also tactless. (51)

40 Minima Moralia. P.247 with alterations in the translation brought in Levin’s Gestures of Ethical Life p.119.

41 Swann’s Way. P.85.

42 Following the Artscroll translation 32:11 “כנשר יעיר קנו על גוזליו ירחף…”

43 Rashi to 32:11 (Translation from The Metsudah Chumash with Rashi Vol.5 p.389.) The effect of Rashi’s comment which renders “מחופף” as “נוגע ואינו נוגע” solidifies the idea that optimal contact is at best a hovering state—the marriage of both extremes. Rabbi Ginsburgh also makes very good use of both the verse and Rashi in driving forward the train of ideas related to prohibitions of touch. See איסור נגיעה ותיקונו. Pp.4-5. Also of note is the comparison of the hovering Eagle with God. In as much as the primary name used for God though out the Torah is י-ה-ו-ה [the Tetragrammaton] which is often rendered as ה-ו-י-ה [Havayah] meaning Being, might we venture a guess that Being (which is not an entity as Heidegger points out) refers to the touching/untouchable, where Being hovers, for just as it is said of God’s “name” “אין לו גוף ואין לו כח הגוף” [‘He has no body nor does he have corporal properties’], so too with Being? What would we touch and what would touch us back? And yet, is not Being specifically what touches us (Dasein) the most? Contact is made not inter-corporally, but from Being to a being, from the Ontological to the ontic. Posted next to these comments, the following Levin quotation underscores the need for a more thorough study of the questions raised:

“If our gestures were to correspond appropriately to their ontological appropriation, they would need to relate to the being of the beings we touch and handle with a tactfulness that leaves their being intact, while also letting their transience, their perishability, and their intangible relation to nothingness become manifest.” (Gestures p.252 on Heidegger Gelassenheit: Tactfully Yielding.)

44 Genesis 1:2 “…ורוח אלהים מרחפת…” See Midrash Raba Bereshit 2:4. “…מרחפת זה רוחו של מלך המשיח…”.

45 By way of Midrash Raba Bereshit 2:4: “נוגעות ואינן נוגעות”.

46 Gestures of Ethical Life. P. 162.

47 “Corpus” in the collection of essays The Birth to Presence. P.192.

48 Being Singular Plural. p.5.

49 Gestures of Ethical Life. P.357. Here Levin is leaning on remarks of Levinas’ in his second magnum opus Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence. See OBBE p.76. Although now is not the time to develop the thesis, Levinas’ expression of the “experience of proximity” carries a certain tempting parallel with the Kabbalist’s notion of the world of emanation or “עולם האצילות” [olam ha’atzilut] where the root of אצילות [atzilut] is אצל [etzil] meaning “proximate.” Thus, the experience of the world of emanation would be an “experience of proximity,” of hovering, of touching and not touching, expressions often used in conjunction with the dynamics of this world.

50 On Touching—Jean-Luc Nancy. P.67.

51Ibid. P.75.

Bibliography

Works in English

- Adorno, Theodor. Aesthetic Theory. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

- Adorno, Theodor. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Translated by E.F.N. Jephcott. London: Verso, 2002.

- Blanchot, Maurice. The Step Not Beyond. Translated by Lycette Nelson. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

- Canetti, Elias. Crowds and Power. Translated by Carol Stewart. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984.

- Derrida, Jacques. On Touching—Jean Luc Nancy. Translated by Christine Irizarry. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

- Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

- Gasset, José Ortega Y. Man and People. Translated by Willard R. Trask. New York: Norton, 1963.

- Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany, State University of New York Press, 1996.

- Heidegger, Martin. What is Called Thinking? Translated by J. Glenn Gray. Harper Collins: New York, 2004.

- Henry, Michel. Philosophy and Phenomenology of the Body. Translated by Girard Etzkorn. Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague, 1975.

- Levin, David Michael (Kleinberg). Gestures of Ethical Life: Reading Hölderlin’s Question of Measure After Heidegger. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. Collected Philosophical Papers. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2000.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 1991.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. Outside the Subject. Translated by Michael B. Smith. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. Time and the Other. Translated by Richard Cohen. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1987.

- May, Rollo. Love and Will. New York: Norton, 1969.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. The Visible and the Invisible. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern University Press 1992.

- Montagu, Ashley. Touching: The Human Significance of Skin. New York: Harper and Row, 1986.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. Being Singular Plural. Translated by Robert D. Richardson and Anne E. O’Byrne. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. The Birth to Presence. Translated by Brian Holmes. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993.

- Proust, Marcel. Swann’s Way. Translated by Lydia Davis. New York, Penguin Books, 2002.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Translated by Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library, 1956.

Works in Hebrew

1) שניאורסון, שלום דובער. יום טוב של ר”ה – תרס”ו. ברוקלין: קהת, 1991.

2) ויטאל, חיים. עץ חיים. ירושלם, 1988.

3)יהודה החסיד. ספר חסידים. ירושלים: מוסד הרב קוק, 1957.

4) כשר, מנחם מנדל. תורה שלמה (בראשית). ירושלים: בית תורה שלמה, 1992.

5) ציננער, גבריאל. נטרי גבריאל הלכות יחוד. ירושלים: שמש, 2001

5) קורדובירו, משה. אור יקר (כרך א). ירושלים: 1962.

Out of Touch (Part 5),

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)